E Pluribus Plures:

El Anatsui

patrick brennan

January 2015

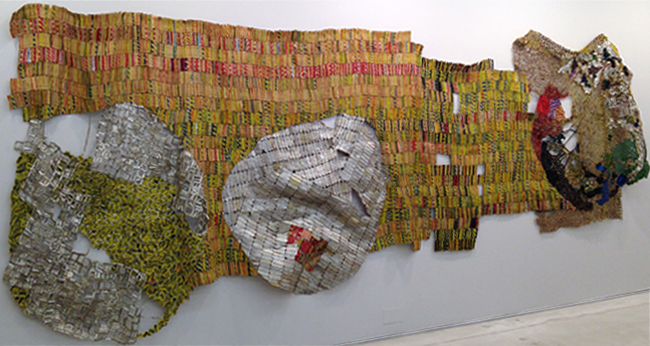

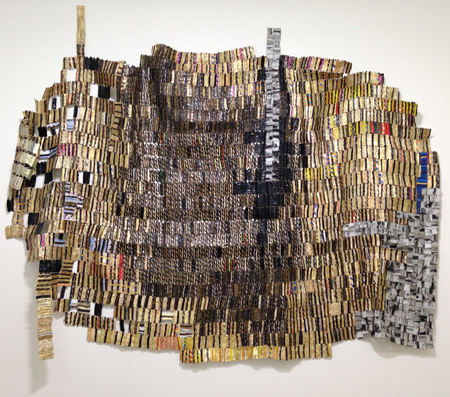

El Anatsui’s gawu constructions (wu + ga : “garment” + “made of metal”), recently visible at both the Jack Shainman and Mnuchin galleries, feel very social to me. They don’t feel univocal. Even though these pieces derive from the decisions of a single artist, the vision doesn’t seem solitary. It’s not that he employs nearly a village’s worth of assistants in their construction (and it didn’t start out like that, by the way), it’s the links of association between each of the tiny constituent parts (usually collected beer and liquor metal container discards). Networks are formed almost tenuously, but certainly flexibly, one to one and one by one, forging lines of affiliation among the parts, connected across degrees of separation. Although this involves the attachment of separate items, this differs in intent and vision from collage, pastiche or bricolage.

Another comparison with artistic actions still pledging fidelity to notions of antecedent pan-European aesthetics & traditions, would be with The Grid, a seemingly unquestioned, automatically accepted a priori assumption adopted in so much art and sometimes praised to no end by the likes of theorist-critic Rosalind Krauss, for example. My constant question to such a practice (especially in its most fundamentalist applications) has been why.

Why so straight? Why always perpendicular? Is this a lack of imagination, a kind of compliance with a dictated order? I recently heard Swoon associate this with the street grids of Manhattan, which adds an interesting suggestion. But still, why does each quadrilateral have to be absolutely identical? And why are all the rows exactly the same width? Is there a reason? Is each identical gesture actually being rethought in a new way? Is each a new discovery, or is this just rote? It does look pretty Henry Ford automaton to me. But then, well, maybe I’m just missing something. These are, after all, artistic choices.

And — it’s not as if there’s an acknowledging of the four directions as have many indigenous Americans, north and south. Nor is there even a hint of the old Western Eurasian earth-water-fire-air quartet. There’s no such sacralizing of space in that gesture — or explicit avoidance of gesture. Nor does The Grid emphasize the gut sensations of horizontality and the upright effort of verticality amid gravity. I instead tend to suspect an imperial eye at work, a Cartesian impassivity, the panopticon cold of quantizing, the elimination of what can’t be classified, the gated community.

I think of what I believe is a Malian phrase that “Evil travels in straight lines” (and I once came across a parallel attributed to the Afro-American south: “The devil works in straight lines”). I think of linear, unquestionable command structures, the Army Corps of Engineers’ 180° damming of the pulsing ecological curvilinears of rivers, or the digitalia of surveillance.

I think of what I believe is a Malian phrase that “Evil travels in straight lines” (and I once came across a parallel attributed to the Afro-American south: “The devil works in straight lines”). I think of linear, unquestionable command structures, the Army Corps of Engineers’ 180° damming of the pulsing ecological curvilinears of rivers, or the digitalia of surveillance.

This is important because Anatsui’s assemblages of fairly equal sized squares, rectangles and hexagons don’t seem to conform to that sort of schema or mentality. Horizontal and vertical rows seem to bend additively rather than in accordance with administratively divisive, preordained design, exampling what Robert Farris Thompson identifies as “apart playing,” where differences, rather than homogeneities, accentuate and clarify through coordinated association. The constructions nevertheless do appear to reference the pan-Western grid that haunts so much of its modern and contemporary art (Skoto Gallery even once opportuned in the ’90s to introduce his work — and successfully so — to New York via a joint exhibition with Sol LeWitt), but the resemblance seems more an incidental one.

Patterns, ideas, memes, if you like, often cross boundaries as homonyms: they may sound the same but don’t necessarily mean the same, especially amid the freedoms of free association. A person may absorb something from “elsewhere,” but it still can’t be but on one’s own terms; it often includes, or is perceived through, something already familiar, a self recognition through the reflected filters of what’s less “home.” The form continues, implies, shapes, suggests, but the context shifts.

In relation to this, part of the freshness of Anatsui’s gawu works emerges from their classificational ambiguity. Their sheetlike two dimensionality greets the eye for painting; and, as soon as they fold, they turn “sculpture.” It’s, in this sense, not really that clear exactly “what” they are. Their presence instead seems more a phase in the discovery of just what they are — or might be, which is, after all, something we may well expect from this process called “art.”

In contrast with his other work in ceramic and wood, it’s hard not to consider here some of the implications of kente patterning. Anatsui grew up Ewe (who, along with the Asante, have been the principal exponents of kente in Ghana for centuries) and, although he didn’t learn that skill, his father wove kente on the narrow strip loom that’s used in this form, which is to say that it wasn’t at all unfamiliar. Long strips about 4-6” wide are woven and then sewn together to form large cloths that before the 19th century were only worn by royalty.

Like Haudenosaunee wampum, these seemingly purely abstract patterns often associate with spoken language. For example, according to the Centre For Indigenous Knowledge Systems, the epie akyi (leopard’s back) pattern accompanies the Akan expression: Kurotwamansa to nsuo mu a, ne ho na efo; ne ho nsensanee no de ewo ho daa. “The leopard only gets wet when it falls into water; the water does not wash off its stripes.”

Like Haudenosaunee wampum, these seemingly purely abstract patterns often associate with spoken language. For example, according to the Centre For Indigenous Knowledge Systems, the epie akyi (leopard’s back) pattern accompanies the Akan expression: Kurotwamansa to nsuo mu a, ne ho na efo; ne ho nsensanee no de ewo ho daa. “The leopard only gets wet when it falls into water; the water does not wash off its stripes.”

But, even when encountering kente from outside its cultural/linguistic context, it nevertheless articulates a distinct visual sensibility; and while Ghana may historically be neither a bread eating culture — nor one that’s inherited a tradition of oil painting — this doesn’t mean that the aesthetic values realized through kente are therefore simply a matter of “craft.” The perpendicularity of most kente composition may relate most directly with the warp & weft conditions of loom generated cloth, but what’s invented within these circumstances is what most distinguishes the practice.

To risk maybe too broadly generalizing about any way of inventing, there seems within a lot of African generated expression an orientation toward activating, emphasizing — or making more evident — the unseen, unsounded or unsaid through sharp, dynamic contrast. Differences so accentuated resonate gaps between, a “something else” — not material, but relational — that can become palpably felt. In a way, these areas of contact elongate within a same space the way fractal complexity is able to lengthen coastline measurements.

East Asian, and especially Japanese, aesthetics also seem oriented toward activating an awareness of such “space,” but through very different strategies; whereas it might also be suggested that the premodernist European in particular tended to most regard space as more or less an inert emptiness just there for a filling with “stuff.”

In this regard, I see The Cut and The Break as principal movers and shakers in kente. These are the accented absences that propel attention toward whatever else may also be going on or coming in. The Break magnetizes a proprioceptive, empty elevator shaft moment: each distinct pattern encourages and generates an expectancy momentum, and a witness’ attention accordingly tends to leap ahead to meet it. But, when The Break intervenes, one’s still feeling a groove that’s also just suddenly disappeared, and Something Else (and what this may be could reach locally toward further invention or all the way to the Invisible Present itself) enters through the gap. These events all together sum a particular kinetic harmonic.

In this regard, I see The Cut and The Break as principal movers and shakers in kente. These are the accented absences that propel attention toward whatever else may also be going on or coming in. The Break magnetizes a proprioceptive, empty elevator shaft moment: each distinct pattern encourages and generates an expectancy momentum, and a witness’ attention accordingly tends to leap ahead to meet it. But, when The Break intervenes, one’s still feeling a groove that’s also just suddenly disappeared, and Something Else (and what this may be could reach locally toward further invention or all the way to the Invisible Present itself) enters through the gap. These events all together sum a particular kinetic harmonic.

This can also be recognized amid the assertive negative spaces of so much African sculpture, in the silent swirls insinuating the continent’s musical beats or among the dancers crosscutting these thresholds. Contraries in kente often meet as horizontal and vertical flows, each with its distinct way to go, each in collision; each asserts askance the crests of the other’s waves, reciprocal, but deliberately not so squared off as to hold symmetrical, given that poised and dynamized imbalance indispensably contributes to motion.

El Anatsui effectively accomplishes an Ornette Coleman on kente. Where O.C. dispensed with song form derived time line grids, Anatsui projectively composes beyond the range of the loom, which isn’t to say that these pieces are all about kente either, but that they are indeed very well informed in that regard. He goes freestyle with the potentials of this sort of composition, encountering possibilities open to continuous variation, growing outward from local interconnections from new perception to new perception. Some pieces resolve to a clear edge but others dither, disperse, meander, dribble off at the frontiers, sometimes open ended, suggesting further developments, open to new suggestions, new ideas, or, like plant growth, simply passing through that current state of becoming.

Distance tells another story: the unfolding liberation of the resplendent. Composed from waste material, they shine. The compositions seem to celebrate demigod-like ideals of a cultivated radiance that’s occasionally reenacted through royal display, but I don’t feel that sort of social hierarchy in these. Any person might glow like this (although this is no 99¢ store pickup glitz). The works shimmer an interior awareness, spread large — and spread public, hence: awe.

When shipborne Europeans began regular contacts with subsaharan African civilizations, they frequently encountered a deeper level of cultivation and higher quality goods and craftsmanship than at home. And, as Walter Rodney recounted in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa that at the beginning of the 16th century:

The king of the Kongo had conceived of possibilities of mutually beneficial interchange between his people and the European state, but the latter forced him to specialize in the export of human cargo. … (He) asked for masons, priests, clerks, physicians, etc.; but instead he was overwhelmed by slave ships sent from Portugal.

The severe damage instigated by those ships still alerts us where the time ingrained habits of pursuing persons as “escaped property” continues to populate a prison industrial complex and make ordinary people wary for very good reason of armed blue uniforms. Neither is the theater of an art world all that free of yet other versions of the property imperative as it teeters between open accessibility to all participants and its service role as a specialized currency broker for one percenters.

Inside these ambiguous conditions of transition, a cosmopolitan Ghanaian, long a resident in Nigeria, is appropriately being accorded the same level of respect and regard as any artist from anywhere else without being tagged as an “exotic.” Meanwhile, I’m still kicking myself for having misread the closing date of his extraordinary 2013 Gravity and Grace exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum and having missed a second look.

Anatsui has also personally reminded us that there are also a lot of other artists doing great work in Africa right now. The open health of mutually beneficial interchange as very reasonably envisioned long ago in Kongo — and a very different world — remains an evolving possibility.