Culturally Capturing the Counter-Culture

John Greiner

September 2016

(The Beat Generation at the Centre Pompidou)

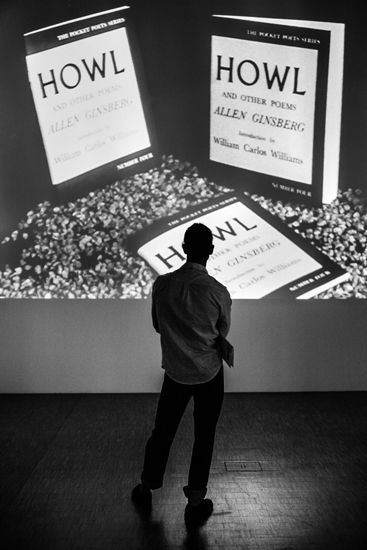

Howl at City Lights, 1957. Black and white silent film © KPIX-TV Bay Archives

Howl at City Lights, 1957. Black and white silent film © KPIX-TV Bay Archives

As with so many rebellions in the realm of the arts the works and ideas that instigated the revolt become museum pieces; whether Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Dadaism, Futurism (in spite of Marinetti’s call for artists to destroy the museums) and even Punk. In the end, no successful counter-cultural movement can escape the assimilation into mainstream culture that occurs when it has succeeded. In its success, the counter-culture’s work is eventually accepted by a wider audience, then lauded by those who were initially critical, finally to be made commercially viable and socially acceptable, hence undermining its initial revolutionary vigor.

The Beat Generation is no exception to this rule. The challenge of mounting a show on the Beat Generation, or on any counter-cultural art movement is to examine the movement in its essential and most vigorous form, before it became a cultural phenomenon, while also having the historical advantage of being able to more clearly discern the triumphs and shortcomings of the movement in its reaction to the cultural mainstream. To be truthful to a counter-cultural movement the curator of an exhibit on that movement must at least attempt to examine it from within and see, as its movement’s members saw, the problems that were prevalent around them and thus forced them to create works in opposition to the norm. The curator must examine what gave birth to the counter-culture, where it came from and how it grew, or continues to grow,

The Beats in their truest essence were American avant-gardists in the tradition of the Transcendentalists and Whitman. It was a movement of vast spaces, both physical and spiritual that sought out freedom beyond the confines of the entrenched culture of the United States at the time. The Beats’ Americanism assaulted the very concept of a complacent consumer America in all of its post-war glory. The United States positioned itself to be the dominant political, militaristic and cultural arbitrator of the western world; the Beats served as a counter to their homeland’s cultural ambitions and in this way their movement traveled the world.

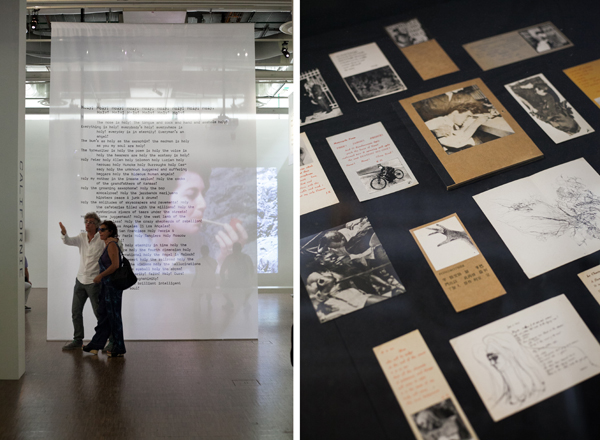

On the Road (original typescript), 1951 by Jack Kerouac

On the Road (original typescript), 1951 by Jack Kerouac

Tracing paper, 22 × 360 cm. Collection James S. Irsay

The quintessential Beat text, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road revels in both the physical and artistic concepts of freedom and the one-hundred-and-twenty foot typescript of the book lies rolled out center stage when one enters the Beat Generation show at the Centre Pompidou, flanked by black and white projections of the passing roadways of America. To the left of the manuscript is Kerouac’s hand drawn map of the U.S.A outlining his planned trip across country in 1947, which would become the source material for the book. Further along there are selections of photography from Robert Frank’s The Americans. This all leads the visitor to this exhibition, from the moment they enter the first gallery of the show, to a recognition of the near infinite potential inherent in the American landscape that was open to the Beat Generation.

Even when the Beat movement journeyed abroad it remained essentially American in its outlook and the national make-up of its members with a few notable exceptions such as Robert Frank, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Bryon Gysin and Ian Sommerville. Paris was one of the major stops for the Beats, so it is appropriate that such a comprehensive exhibit of the movement be mounted in the city. Curators Philippe-Alain Michaud, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Rani Singh and Enrico Camporesi do an admirable job in their examination of the Beat Generation at the Centre Pompidou while not undermining the movement’s initial artistic vigor. The Beats were never stylistically cohesive, so it is natural that the curators would have a number of diverse routes to traverse in an attempt to give the visitor an overview of what these artists were hoping to achieve. One of the debatable points that the curators make is that the Beat Generation came together for two reasons; the 1943 meeting between the then fifteen-year-old poet Philip Lamantia and the godfather of surrealism, André Breton and the friendship that began around the same time in New York City between Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs. Though the curators credit the meeting of Lamantia and Breton as being one of the primary causes for the birth of the Beat movement, the logic and historical accuracy of this assertion is specious, being that Lamantia did not connect with the core Beats until the famed reading at the Six Gallery in 1955 and by this time he was long past Breton and orthodox surrealism. However, this assertion does allow the curators the opportunity to expand their concept of the Beats and move it into the realm of the international avant-garde.

The Beats were artistically primarily a literary movement and there are a number of manuscripts in the show such as the previously mentioned typescript of On the Road, as well as works such as Gregory Corso’s “There is No More Street Corner”, Ginsberg’s “Kaddish” and “Howl” and LeRoi Jones’ “The Occident. A Poem to be read at Bob Thompson’s Funeral” and various magazines and nearly a full room of Allen Ruppersberg’s The Singing Posters, but unfortunately, literary works cannot sustain a museum show. There are numerous archival photographs by Allen Ginsberg, Fred W. McDarrah, John Cohen, Joanne Kyger and Harold Chapman, as well as paintings and drawings by Larry Rivers, Julian Beck, Alfred Leslie, Bryon Gysin, Burroughs and Kerouac. A large portion of the show, and what seems to be the primary focus of the curators, in an attempt to keep the attention of the viewing audience is film.

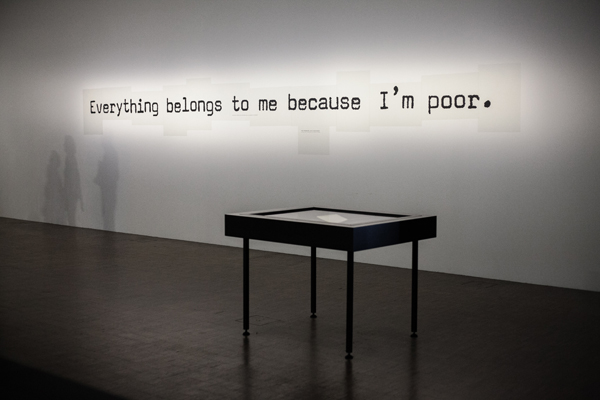

The Singing Posters, Allen Ruppersberg

The Singing Posters, Allen Ruppersberg

There is a certain joy in being in the midst of a space where when turning first to the right and then to the left, one is able to watch Taylor Mead perform in the Ron Rice films The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man and The Flower Thief. It is in the realm of film that the curators move towards a very liberal definition of who made up the Beat Generation. It is easy to make the point that Robert Frank, who was a close Beat affiliate, especially with his films Pull My Daisy and Me and My Brother was a part of the Beat movement. A case can also be made for D.A. Pennebaker inclusion based on the opening sequence of Don’t Look Back in which Allen Ginsberg appears in the background while Bob Dylan drops cue cards to the ground as his song Subterranean Homesick Blues plays. There are other filmmakers in the show such as Harry Smith, Stan Brakhage, Larry Jordan and Bruce Conner who were connected to the Beats in a much more loose manner, and should be considered more of a part of the non-Beat Generation avant-garde.

Me and My Brother, 1965-1968 by Robert Frank. 35 mm black & white film

Me and My Brother, 1965-1968 by Robert Frank. 35 mm black & white film

Collection The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and Robert Frank

By focusing to excess on film some of the actual members of the Beat Generation are excluded from the show, including Jack Micheline and Ray Bremser. Another unfortunate miss on the part of the curators is their cursory examination of the contribution of women to the movement. The Beats have long suffered from the stigma of being a male-centric group and the Pompidou exhibit does little to destroy this perspective despite the role that women played within the movement. There are brilliant and provocative works by women in the show including Diana DiPrima’s Haiku, ruth weiss’ Gallery of Women, photography by Joanne Kyger and Penny Arcade’s reading of “No Mona Lisa” on John Giorno’s Dial-a-Poem where she proclaims

I am no collector’s item,

no curator’s pet.

The Dial-a-Poem Album – I Am That I Am, 1968-1972. Installation of 4 telephones by John Giorno.

The Dial-a-Poem Album – I Am That I Am, 1968-1972. Installation of 4 telephones by John Giorno.

At left, Planche B # 6, Saint Louis, 1964. Above right, Targets on Cardboard, 1967, both by William S. Borroughs

But there is more than enough room in an exhibit that establishes a very fluid concept of what makes a Beat, to examine the work of women in and around the Beat movement. If one is to include the paintings of Larry Rivers in the show because of his participation as an actor in Pull my Daisy then the same should hold true for Alice Neal who is also featured in the film. If Julian Beck’s work is included in the exhibit, then so too should be the work of Judith Malina, who had a more substantial impact on the avant-garde and the experimental than her husband Beck. Of the younger generation that came after the first wave of the Beats, there is no real acknowledgement of Anne Waldman in the show or the Burroughs’ influenced Kathy Acker.

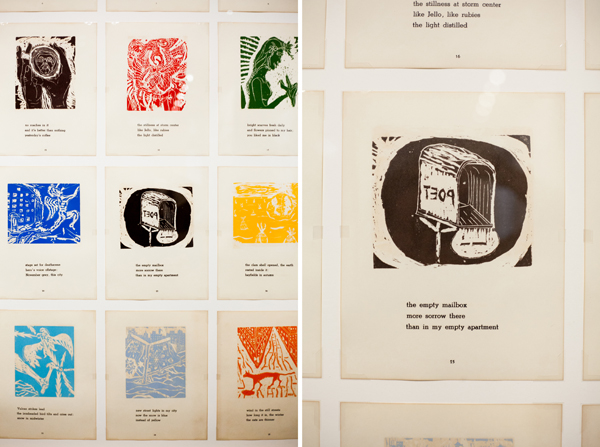

Haiku, Topanga, The Love Press, 1967 by Diane di Prima, illustrated by George Herms

Haiku, Topanga, The Love Press, 1967 by Diane di Prima, illustrated by George Herms

The exhibit progresses through the Beats’ travels through New York, San Francisco, Mexico, Tangier and culminates in Paris, where the movement perhaps reached its most experimental heights with the works of William S. Burroughs and Bryon Gysin and their usage of cut-ups, and also in the creation of the Dream Machine. Burroughs, much like de Sade, strove for a freedom without bounds which would lead to an essential truth that in the end could not be codified, manipulated and undermined. For the Beats, freedom was the truth, whether it was from the confines of place or the mind. The Beat Generation exhibit at the Centre Pompidou is not simply an examination of one particular counter-cultural school of thought, rather, it is an examination of the various roads to artistic freedom. The curators’ compilation of art and artifacts, which is both impressive and overwhelming, is greater than the sum of its parts. What the Beats created still continues to influence in spite of its acceptance into mainstream and the potential cultural neutralization inherent in such an acceptance. The ideas and art put forth by the Beat Generation still have a freshness about them that can never be bound by a classroom or a museum, no matter how hard the academics and art and literary arbiters may try to place them into the mainstream of cultural history. The vitality inherent in this fact defines the Beat Generation. The artistic vigor of the Beat Generation will be felt for generations to come.

The Dial-a-Poem Album – I Am That I Am, 1968-1972 by John Giorno

The Dial-a-Poem Album – I Am That I Am, 1968-1972 by John Giorno

Images courtesy of Carrie Crow

Beat Generation

Centre Pompidou, Paris

June 22 – October 3

https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en

Such a great piece with real insight to the successes and challenges curators faced presenting this work. Of particular interest was the analysis of what the legitimate origins of the group were and who curators chose to include/exclude. Well done.