Interview with Keerti Pooja

Colette Copeland

March 2024

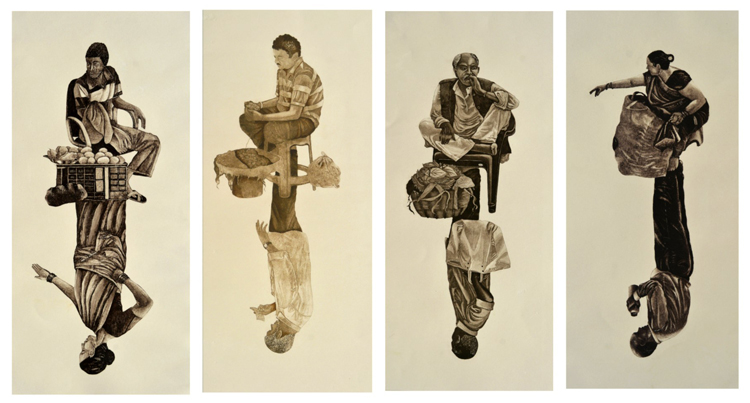

Perpetual Itinerary, Etching Aquatint, 90x50cm, 2020, image courtesy of Champa Tree Gallery

I first learned about Keerti Pooja’s work during a weekend visit to Delhi last September. I was visiting Champa Tree Gallery and her work was part of the group exhibition A Room Full of Ph**ls. Unlike most commercial galleries, Champa Tree supports young, emerging artists. When the artist joined the gallery, she was still completing her master’s degree in printmaking. At 28 years old, she is the youngest artist represented by the gallery. I had the pleasure of chatting with her at the gallery during the Delhi Art Fair, which is the largest international art fair in South Asia.

Colette Copeland: Your work addresses issues of migration and invisible labor. I was thinking about these issues within the framework of my own research—how artists are exploring themes of borders and boundaries in their work. We discussed your large watercolor composition Collecting Memories which is currently on display at Champa Tree. The invisible boundary between the people who labor and those who consume, as well as the “fruits of the labor” equating to a greater value than that of human toil. You depict this so beautifully with the subversion of scale in the work, with the objects dominant and the people painted in miniature. This also references the history of miniature painting in India. Please expand upon the ideas of borders and boundaries in your work as it relates to community and labor.

Kerti Pooja: In Collecting Memories, I paint the people in miniature to show life slowly unfolding to reveal what is hidden beyond the surface. I strive to capture the essence of places and people, and the diverse gush of emotions. Speaking about borders and boundaries in my work, it’s a metaphoric representation—to show people’s gestures and lives, which are typically hidden or invisible to many people. My visual narration becomes tales of individuals representing deep conversations with the objects they carry. The intrinsic intricacies of their belongings represent their journey.

For me, it becomes the embodiment of what they carry within them. Though the people, their migration and movements hold an intense sense of accumulated chaos, it is the conviction in them that intrigues me. As I observe people, witnessing the language in which they sustain and what they carry, it evokes in me a deeper story. The denser the objects appear, the more layers of their stories unfold. The objects hold an innate ability to tell stories; they become a unique visual chronicle. The piled objects covered in potlis (bundles) create an intriguing fabric and reveal what is hidden beneath them. My series of paintings are the deep conversations with these glances. As I journey through my paintings, I transfer the sense of calmness within the chaos that unveils the true essence of life. And I often wonder how people dwell in the constantly changing uncertainties with balance and ease, which I depict through my work.

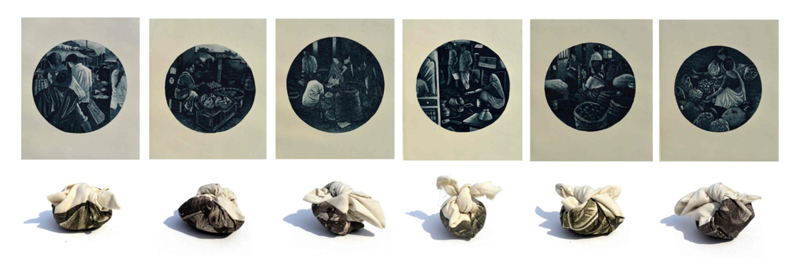

Within the Boundaries, Etching Aquatint on paper & cloth, 30x120cm, 2020, image courtesy of Champa Tree Gallery

CC: Your intentional choice of materials adds additional context to your work. You often work in sepia, which symbolizes the earth. The Wasli paper comes from Jaipur, a unique, handmade tradition from generations of one artisan papermaking family. In the series Within the Boundaries, you print on “potlis”, the cloth bundles used by workers to transport goods. How does your choice of materials inform the themes of invisible labor and tradition?

KP: My work’s visual imagery revolves around several nuances that bind it together. The form, materials, and techniques I have connected with for the past several years support the conceptual narrative of my art. My work is monochromatic using a sepia tone in conjunction with the Wasli paper. This ensures visual consistency aesthetically, and with the visual narrative. Wasli is a special type of handmade paper that was historically used by miniature painters in the past and is still in use today. This paper connects me in a very personal manner to the history of painting. The natural rawness and richness of Wasli excites me with curiosity, because each blend of paper is slightly different, always yielding a surprise.

Color is another fundamentally important aspect for me. I have always felt that one shade has a billion shades. Since my undergraduate degree, I have been practicing with monotones of aquatint, a printmaking practice that inhibits the character and quality of merging layers of tones. I love the monotone shades of the works and sepia specifically because it is a mixture of many colours. The color of the earth is brown and yet as universal as it sounds, the brown color of soil consists of thousands of shades diversely connected to varied geographic places. The ochre yellowish-brown sands of the deserts, the brown of the moist soil during the first rain, and the deep browns of the forests. I do use many colors in my paintings but do so with subtlety.

Amongst the many objects I have seen in bazaars, the people carrying Potli- a cloth wrapped around objects, calls my attention. I imagine what hidden treasure it carries. On top of the Potli a knot is tied and what is hidden beneath is always a mystery. Something secret and sacred which holds valuable significance. Potlis has been in India since the beginning of time, a very simplistic way of wrapping and keeping things.

My recent thought processes and explorations with these subjects have been to make an etching print on cloth and tie it like a Potli. The beauty about wrapping things in Potli is some things are seen and some things aren’t visible. Like Potli of a seller or a street vendor this creates a beautiful symmetry.

CC: In our discussion, we spoke about underlying narratives in your work. Creating an open-ended narrative is one aspect that draws me into looking at the work multiple times. The current exhibition at Champa Tree is entitled Weavers of Contemporary Narratives. How are you approaching the concept of both contemporary visual storytelling, as well as re-writing the dominant narrative present in contemporary Indian culture? I am specifically thinking about the etching work which shows the connection between the laborer and consumer and how you invert their positions but also showing their interconnectedness.

KP: The subjects that I showcase in the paintings include objects, object sellers, vendors, and flower sellers. I like to capture the hustle and bustle of the bazaar. When I speak with the vendors they have a lot to say. They are probably happy to be heard. Their eyes sparkle and their faces communicate their unheard stories, as they proudly own their lives. But silence is also a great storyteller. Sometimes even silently observing them narrates tales of their lives. These observations have led me to think about objects and people deeply.

I have been an observer of the objects that people carry with them. The lives of objects speak beyond just the material, it gives a sense of belonging. Some objects are purchased, some are inherited, and some are sold. I feel that all objects are cherished by people. I visit the Shukravari – Friday Market in Vadodara where second-hand things are sold. One buys what the other has discarded and the chain continues. My artworks are layered with objects juxtaposed side by side with people. Their stories intertwine, forming a loop of sorts.

Some works show an invisible line which is somewhere drawn between the sellers and buyers, where a person’s internal perspective of life may not always match up with the reality around them. I see this as a metaphor for the methods in which one shapes their world. It reveals the fantasy and exploration of the everyday turned upside down.

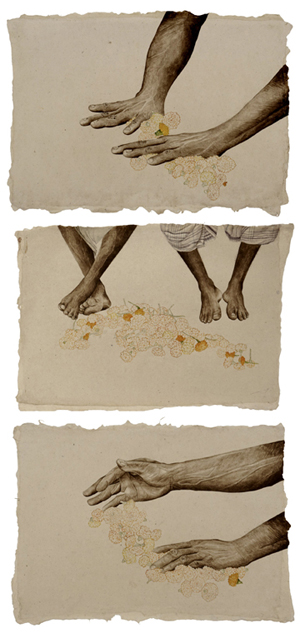

Collected Frangrances 1, Watercolor on Wasli

Paper, 18×12 in. each, 2023, image courtesy

of Champa Tree Gallery

CC: In the Collected Fragrances series, you leave parts of the composition unfinished emphasizing how certain forms of labor are performed outside of public view, thus rendering them unacknowledged or under appreciated. I’ve been thinking about how this impacts culture from a socio-political and economic dimension and/or reinforces separation in class and caste. Please expand upon these ideas in this work and your other series.

KP: In the series Collected Fragrances, I paint marigolds and mogra in their natural vivid colors, which contrasts the rest of the monochromatic composition. I connect with the tones of Indian streets. Sometimes amidst the dry air, something pops out and catches my eyes. Similarly, sometimes I miss key details when observing labor on the street. The unfinished parts of the compositions reference these “missed” or unseen moments. Laborers and their work often are not visible to the front line of society. They are observed only when they are needed. The streets of India and the bustling bazaars continuously talk; they are full and always moving. I try to capture a detailed mental picture of people who are there amidst the tones of people and activities in the background. One can get lost in the sepia tones of my work, but once observed closely, there are colorful characters that come alive to narrate their stories through the many objects they carry.

As part of her Fulbright Research Award in India, Colette Copeland has been doing a series of interviews with socially engaged artists whose work explores themes of borders and boundaries.

Interview with Hiten Noonwal →

Interview with Parvathi Nayar →

Interview with Manmeet Devgun →

Interview with Moutushi Chakraborty →

Interview with Riti Sengupta →

Interview with Jyotsna Siddharth →

Interview with Mallika Das Sutar →

Colette Copeland is an interdisciplinary visual artist, arts educator, social activist and cultural critic/writer whose work examines issues surrounding gender, death and contemporary culture. Sourcing personal narratives and popular media, she utilizes video, photography, performance and sculptural installation to question societal roles and the pervasive influence of media, and technology on our communal enculturation.